Imran Shauket

The modern day Pakistan of 77 years age continues to struggle to find its rightful place in the world, without much success. Yet, the Pakistan of 2000 years ago continues to rise in prominence in the eyes of the world. More accurately, the Buddhist civilization of Gandhara (3 BCE onwards), now cradled primarily in the northern areas of Pakistan, beckons the world to visit its grand sites and study its unparalleled and magnificent past. And it seems that almost every few years, an archaeological find of epic proportion in Gandhara brings renewed attention to this historic culture. One such find has been dubbed the Buddhist equivalent of the Jewish “Dead Sea Scrolls” of Gandhara. It is a coincidence that they both date from roughly the same time period in history.

Recently, I was fortunate to meet an extraordinary individual, Dr. Mark Allon, of the University of Sydney. Whereas many of us have been promoting Gandharan heritage of Pakistan to the world, focusing on the historic sites, stupas, monasteries, art and sculptures, unbeknownst to us, there is an even more unique facet of this heritage which is unparalleled and cannot be overstated. This facet is the focus of the work of Dr. Allon and his colleagues, and it has to do with the preservation and translation of Buddhist manuscripts discovered in the recent past in Pakistan. Notably, these manuscripts are in Gandhari and Sanskrit. Sadly, the earlier discoveries of these historic manuscripts found their way into collections in Britain, Europe, North America, and Japan via the antiquities trade, a terrible loss of cultural heritage to the descendants of ancient Gandharans who produced them (Allon 2022). It should become a national endeavor to have these returned to Pakistan, or at a minimum, have them electronically documented and preserved in a library focusing on Gandharan literature. There are many well-wishers of Pakistan who would support this including the visionary Abbot MV Arayawangso of Thailand, and the incomparable Chief Abbess, MV Jue Cheng of Malaysia. But I digress.

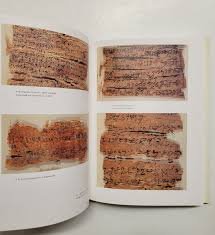

The aforementioned manuscripts that Dr. Allon et al are working on are birch bark scrolls containing texts in Gandhari language and Kharoshthi script. They date from 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE. Hence they represent the oldest Buddhist and South Asian manuscripts yet discovered. Long have we touted Taxila and Gandhara as the first seat of learning, a university, in the world! Now, we have proof that Gandhara indeed gave birth to the oldest Buddhist writings and manuscripts. More importantly, these scrolls appear to be of local compositions rather than texts translated into Gandhari from works composed elsewhere. So these stories, texts and scripts are wholly and truly from this region – original thoughts and versus of Gandharan Buddhism.

Beyond conservation and translation of the manuscripts, Dr. Allon’s initiative is also creating curatorial facilities for the conserved manuscripts at the Islamabad Museum. They will also train local conservators which will enable Pakistan to conserve other manuscripts. Finally, the collection will enable Dr. Allon and his colleagues to train Pakistani students to study these ancient languages by establishing full Gandhari and Sanskrit language teaching programs at local universities. Imagine, young Pakistanis learning the languages of their forefathers from 2000 years ago!

In a further phase of this project, these manuscripts will be published and made available for worldwide audience, as well as local communities. This will include making select materials available in Urdu and Pashto. These publications will generate further interest in Gandhara and will take forward Pakistan’s ambitions to create a Gandharan pilgrimage based mega-tourism sector which could generate USD 30 billion in income for Pakistan.

Neither an academic, nor a particularly couth individual, I was yet awestruck looking at these 2000 year old fragile pieces of bark with beautiful writing on them. The writing was delicate and flowing, and some manuscripts showed small figures of Lord Buddha used within the text as some kind of punctuation. While witnessing the painstaking work that these guests of Pakistan (Mark from Australia, Mary from Boston, and Vania from Portugal) were doing to preserve the history of Pakistan for generations to come, I wondered if we could challenge the many Pakistanis – bureaucrats, officers of archeology, private collectors and particularly the men of the highest rank of uniformed services – who have taken manuscripts, artifacts and arts of Gandhara into their personal collections. What if they were to create proper private museums established with official assistance and display the private collections to share with the world? Otherwise, these “collectors” would enjoy these monuments to history for a very finite time and who knows if their descendants would even care about these private collections. They will probably end up being cast aside or discarded over the years to come. You, the collectors, are not going to live for long, but you can leave a legacy lasting centuries.

The writer is a former Senior Advisor to the Government and a sector development specialist. He is also a promoter of Pakistan and its Buddhist heritage.